Research Project Artifact Inventory LIT 6396 Scholar: Blake Vives

My Artifact:

Trimmer, Sarah. Fabulous Histories, Designed for the Amusement & Instruction of Young Persons. Philadelphia: Gibbons, 1794. Print

The modern editions of my novel exist in these forms:

Trimmer, Sarah and Legh Richmond. Fabulous Histories. 1786. New York: Garland, 177. Print. This edition has a preface by Ruth Perry and includes the story The Dairyman's Daughter, by Legh Richmond with a preface by Gillian Avery.

Demers, Patricia, and R G. Moyles. From Instruction to Delight: An Anthology of

Children's Literature to 1850. Toronto: Oxford UP, 1982. Print.

Trimmer, Sarah. Fabulous Histories. Farmington Hills, Mich: Gale, 2005. Web.

o GALE offers the 1786, 1791, 1798 editions in an online format.

· My text is not in the Project Gutenberg Database, however, I did find a Google Books link to the 10th edition published in London in 1815:

·

A search of the APS Database

revealed: (I realized that “fabulous histories” was a common phrase in

early America.)

o

In 1820 the Ladies Port Folio published an article

about Trimmer’s life and accomplishments.

o

In 1807 my text

was listed as a new publication by the Christian

Observer, a Boston newspaper.

o

I found a

positive review of the 1822 Boston edition of my text. The review was published in 1826 in the American Journal of Education.

o

In Children's Literature of the Last Century, which

was published in 1869, Trimmer is

hailed for her ability to write a story that actually entertains children. The author speculates that she was inspired

by Rousseau, and calls her the parent of your literature in England.

o

In reviews or

book lists the text is listed as “18 mo.” This might mean it was published in

monthly increments over 18 months.

o

In the American Publishers' Circular and Literary Gazette

(1855-1862); Jan 19, 1856; it is

listed with “126 boards” and “1s” next to it.

I have no idea what this means.

o

The Christian Register and Boston Observer notes in 1835

Trimmer’s contribution to the improvement in children’s Sunday school education.

Q: When, where, and by whom was your artifact first printed?

A: Printed and sold in Philadelphia in 1794 by William Gibbons.

|

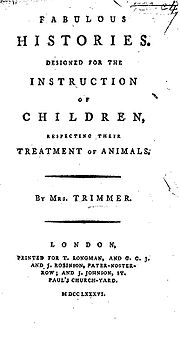

| Title page of the London edition. |

- The writings, of Thomas Paine,

secretary for foreign affairs to the Congress of the United States of

America, in the late war. Containing, Common sense, The crisis, Public

good, Letter to Abbe Raynal, Letter to Earl Shelborne, Letter to Sir Guy

Carlton, Letter to the authors of the Republican, a French paper, Letter

to Abbe Syeyes, Rights of man, part I. Rights of man, part II. Letter to

Mr. Dundass [sic]

- A vindication of the rights of

woman: with strictures on moral and political subjects. By Mary

Woolstonecraft [sic].

Because he lived in

Philadelphia in the 1790s it is likely that Gibbons was a Quaker. He also published this Quaker text, which had

an advertisement at the end for a different Quaker text also published by

Gibbons.

The means, nature, properties and effects of true

faith considered. A discourse delivered in a public assembly of the people

called Quakers. By Thomas Story. (Evans 46881)

Q: Did your

artifact appear in print at any time in the 18th or 19th

centuries?

A: Yes. Here are the reprints listed by WorldCat:

London printings: 1786, 1788,

1791, 1793, 1798, 1802, 1807, 1808, 1811, 1815, 1817, 1818, 1819, 1821, 1822,

1826, 1830, 1831, 1833, 1834, 1838, 1844, 1845, 1847, 1848, 1850, 1852, 1853,

1855, ~1860, 1862, 1864, 1867, 1870, 1875, 1877, 1878, 1880, 1897

Dublin printings: 1786, 1794, 1800, 1808, 1819

France printings: 1789, 1799

Germany Printings: 1788, 1845

Philadelphia printings: 1794, 1795, 1869

Boston printings: 1822, 1827,

1901

1818 London edition.

What speculations

can I make from such a long print history? Well, the text I have is one of six

American editions. The text was

obviously popular in London; I was amazed that it was in print for about one

hundred years in London. Perhaps, the

influence of this story is evident in British culture today. The major differences between the texts seem

to be the dedication and introductory material.

However it is interesting that the modern reprints were in New York and

Toronto. So, it must have made a lasting impression in the new world to. The fewer early American print dates do not

necessarily mean the book was not popular because in early American book

culture it was popular to circulate one copy of a book amongst many people.

Q: What was

the actual size of your artifact in inches or centimeters? What information can you find about its

physical presence, binding, etc.? Do you

think it was expensive or inexpensive?

Can you see a price?

A: The

measurement of my artifact given by Evans

is 16 cm and the bindings are described as “quarter bindings” and “marbled

papers (bindings).”

On the website alibris.com I

found a glossary of book terms and these definitions:

“Marbled paper - Colored paper with a veined, mottled, or swirling

pattern, in imitation of marble, which is used with paper-covered boards and as

end papers in books. The use of marbled papers was especially popular during

the Victorian era.”

“Quarter-bound - A book with a leather spine and with the sides

bound in paper or cloth.”

Even though I cannot see a

price on the digital copy, by taking into account the marbled paper and leather

spine binding I believe the book would have been expensive.

Q: View the

original title page using the digital database or microfilm. What is included there?

A: Here are the exact words of all of the information listed on the title page:

FABULOUS HISTORIES,

DESIGNED FOR THE,

Amusement & Instruction

OF YOUNG PERSONS.

BY MRS. TRIMMER.

PHILADELPHIA

PRINTED AND SOLD BY WILLIAM GIBBONS.

1794

Q: If there is more than one edition, compare the title pages. Note any differences here and keep PDFs of these pages, if possible.

A: For the

two available American editions available on Evans the book seems exactly the same, with the exception that the

later edition is missing the title page and many pages are torn. Maybe the later edition being torn and

worse-for-the-wear shows that it was widely read and circulated. It is not

until years later that engravings and pictures are added to the title page.

Q: What miscellaneous front matter exists? Describe it:

A: Frontispiece:

sadly, there is no frontispiece to this edition.

Engravings: none. There

are chapter engravings in later editions that I found on Google Books.

Preface: The preface is written

and signed by Trimmer explaining

that the idea to write an instructive story with talking animals came from her

children, who insisted that animals talked to them. She says that she hopes to save innocent

animals from the abuses of children with her book. Because she writes the preface herself

(instead of a man) I believe that she had a lot of authority as a writer in

London.

Dedication: The dedication is “to Her Royal Highness Princess

Sophia.” Apparently the book was presented to the Princess Sophia when she was

a child and Trimmer says that she will gain honor by presenting the book for

her to learn from. I found Princess

Sophia on Wikipedia and learned that she was a born in 1777 to King George III

and Queen Charlotte which means when the book was first published in 1786 she

was eleven years old. This dedication

could explain that Trimmer’s authority as a writer comes from her connection

with the royal family.

Q: How long

is your text? How is it subdivided

(chapters? Volumes?) Is the print large

and easy to read or dense, with many words on each page and lines close

together?

Q: What back

matter exists (following the end of a text, usually signified by the word

“finis”)? Sometimes lists of subscribers

or other works from this printer or bookseller are mentioned here.

A: There is

no back matter and there are no subscribers because the publisher basically

copied the book from the London edition.

He would most likely not have needed upfront funding for a book that he

knew would be popular because it was an already popular book from London.

Q: Are there

other texts like yours, and how can you tell?

A: I

searched for Sarah Trimmer in Evans and

found a text called:

An

easy introduction to the knowledge of nature. Adapted to the capacities of

children. By Mrs. Trimmer. Revised, corrected, and greatly augmented; and

adapted to the United States of America.

Because this was edited especially for American audiences and printed in Boston

two years after the first edition of Fabulous

Histories, I think Trimmer’s first book must have been extremely popular

for her to write an American edition of another book. If the Boston printer saw that Fabulous Histories was selling well in

Philadelphia he might have seen an opportunity to profit and contacted Trimmer

and proposed she write the new edition to her other book.

Q. What is the relationship between your

artifact and structures of power in early American culture (and how can you

tell)?

A: I

currently believe that my book was acceptable to the power structures in early

America because it was printed many times and other books by Trimmer were also

printed in America (including a Sunday school manual with pictures). However, I believe that some people might

have taken offense to Trimmer’s “naked” presence in the book; what I mean is

that she had no male sponsors to endorse her in the frontmatter in the London

edition that was reprinted in America. I

assume this because the changes made to her other book (printed in Boston as a

special “American” edition) were essentially to add a third-person preface

describing how the content was approved by a “Dr. Watts.” There is no name signed to this, but it does

stand in stark contrast to her earlier book that included her dedication to

Princess Sophia and her message to the readers.

Grenby, M.O. “‘A Conservative Woman Doing Radical Things’: Sarah Trimmer

and The Guardian of

Education.” Culturing the Child,

1690–1914. Ed. Donelle Ruwe. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow P, 2005. ISBN 0-8108-5182-2.~Blake